‘Quarantine’ walks an uncomfortably thin line

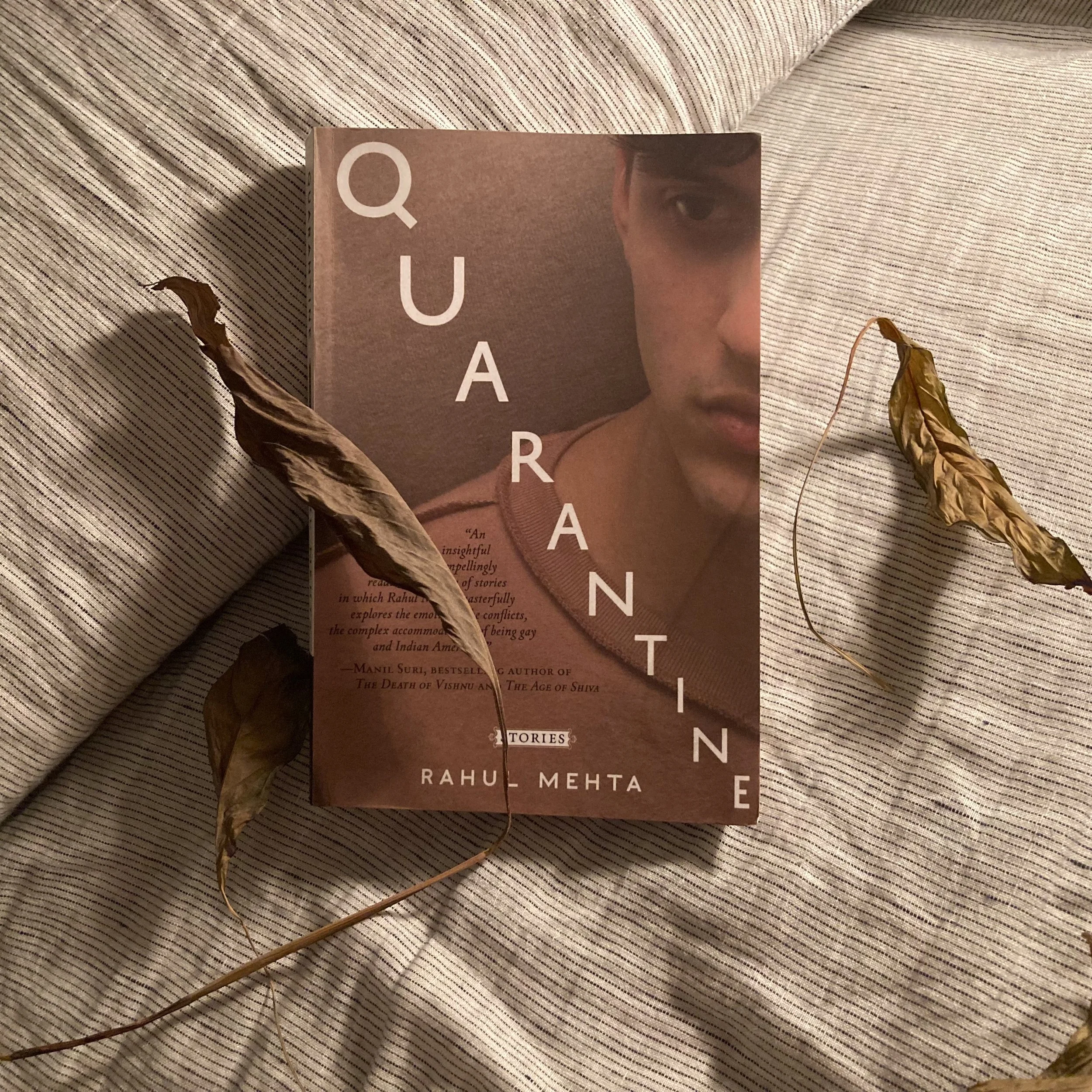

Rahul Mehta’s 2011 short story collection came to me during a time when the word quarantine had a uniquely powerful meaning. I expected a book about being trapped inside the world of one’s hometown, unable to move forward or back, forced to introspect and comb loose the knotted strands of a life that’s become matted with confusion and contention. In a way, that’s what this book presented, though in a different way than I anticipated.

This book is a meditation on frustration and on the experience of feeling trapped, repressed, and too tired to treat the people around you with kindness. It’s a long Thursday-afternoon-in-a-dentist-waiting-room of the soul. Each character sits on a border between one state of being and another: partnered to single, spiraling to stable, hiding to revealed. Only very rarely does Mehta leave us with any notion that the transition will ever resolve. Usually, another state begins to change long before the current one solidifies, such that the lives of the characters become barber poles of uncertainty.

Mehta’s narrators are often self-destructive, to the point of frustration. To read this book is to be confronted by the profound lack of mental health resources available to the general public in the early 2000s, and by a version of queer America that reverbrates more deeply with the legacy of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Underlying each story is a sense of desperation. Will we be able to keep our grandmother in the United States, or will a new administration deport an old woman suffering from dementia back far away from all her children? Will the narrator ever gain control of his own actions, or will he always be governed by his self-destructive impulses? Will anyone ever move on from the past, or are we all trapped in eddies we’ll never escape?

This is not a book you read in one sitting unless you have the emotional fortitude of a fifth-century hermit saint. It challenges on multiple levels, not all of them wholly edifying. The pathos of the work itself is very powerful, quickly gripping the reader and drawing them forward through the pages; it’s almost a morbid curiosity to see what will fall apart next. Unfortunately, it flirts at the corners of the “Appalachia as regressive backwater” narrative. This leads the reader into a confrontation with the problem of privilege. A decade later, we might resent the characterization of the region. But at the same time, it’s hard to blame a gay Indian American man for scorning the place he grew up. It’s hard to judge from the text whether Mehta intends to convey that scorn–perhaps he tells these stories from a place of greater stability and compassion than his narrators exhibit. But within the text, the reader is forced to live with that uncertainty.

This is not, per se, a pleasant book. It’s definitely a good book, in that it communicates what it sets out to communicate. It’s a work whose arguments should be considered in the broader conversation of Appalachian literature. It’s important. It is also, in the literary sense, a tragedy–and should be regarded as such from the outset. Readers who enjoy tragedies will enjoy the experience. Those who don’t should probably read it anyway.